Combat Breathing

There is not occupation of territory, on the one hand, and independence of persons on the other. It is the country as a whole, its history, its daily pulsation that are contested, disfigured, in the hope of a final destruction. Under these conditions, the individual’s breathing is an observed, an occupied breathing. It is a combat breathing. From this point on, the real values of the occupied quickly tend to acquire a clandestine form of existence. In the presence of the occupier, the occupied learns to dissemble, to resort to trickery.

— Frantz Fanon

Every day, tear gas canisters are fired somewhere in the world. But while in the Global North activists may be exposed to gas during demonstrations, it is not an integral part of their everyday life. In contrast, in places like the Palestinian refugee camps in the West Bank, gas grenades are fired several times a week, and in some months, daily. So the residents had to adapt to its horrid, noxious presence. The first line of defence against the gas is to wear a breathing mask. Protesters usually do not have access to the right equipment and are forced to make their own gas masks from materials available to them – plastic water bottles, soda cans, old T-shirts. This is a grassroots, consistent upcycling against toxicity of the state and systemic oppression. Now that police brutality and gas abuse are on the rise, we can learn with and from those who have been resisting for years.

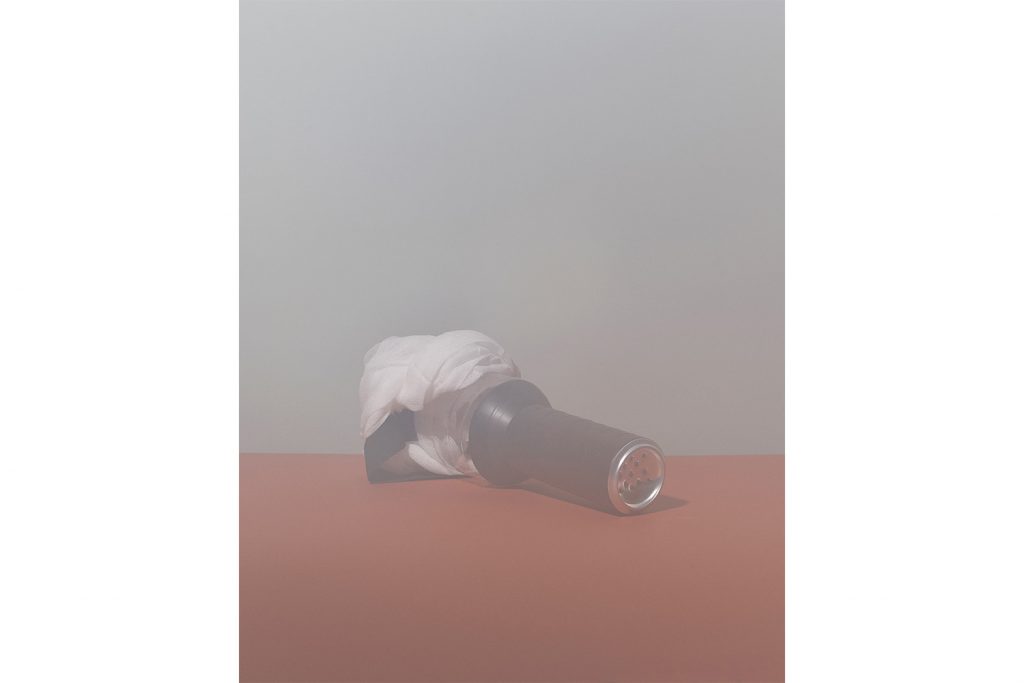

2. Replica of a mask from protests in Myanmar, 2021.

3. Replica of a mask from protests in Venezuela, 2017.

4. Replica of a mask made by a Palestinian boy in Gaza, 2019.

5. Replica of a mask from Venezuela, 2017.

Project

Comissioned by:

Political Critique, Jasna 10, Warsaw (PL), 2021.

Exhibition:

Motion That Comes Back to the Body

Bunkier – Gallery of Contemporary Art, Kraków (PL)

09.2025-01.2026

Collaboration

2025:

Curator: Marta Lisok, Agnieszka Sachar

Film:

Featuring: Mustafa Mustafa, Gaza

Director of Photography: Przemysław Brynkiewicz

Editing: Celina Przyklęk

Sound: Konrad Smoleński, Rafał Nowak

Colour correction: Jarek Sterczewski

Translation: Kamila Mustafa

Titles: Studio Lekko

Special thanks: Jagoda Szelc, Grzegorz Pamrów

2021:

Curator: Wojtek Zrałek-Kossakowski

Production: Kuba Rudziński

Illustrations: Marcin Kubiak

Photos: Grzegorz Wełnicki

Objects

Film 11′

7 masks: plastic bottles, cans, activated charcoal, onions, insulation tape, cotton, rubber band;

Illustrated instruction

Against toxicity of the state

The project Combat Breathing takes this history as a starting point, focusing on the resilience and creativity of communities who develop grassroots methods of protection in the face of chemical repression.

Anybody wanting to grasp the originality of the era has to consider the practice of terrorism, the concept of product design, and environmental thinking, writes Peter Sloterdijk in Terror from the Air. For him, the convergence of these three elements defines the modernity of the last century—beginning, in his view, on 22 April 1915 in Ypres. On that day, German forces released chlorine gas against French soldiers, marking a radical shift in how war was waged. This was not merely a new weapon, but a new logic: a turn from conventional warfare to environmental terrorism. Terror from the air began an era in which the target of an attack was not only the body of the enemy, but the very atmosphere around them. From that moment on, what would be attacked in both war and peacetime would be the conditions necessary for life1.

Terror operates on a level beyond the naïve exchange of armed blows between regular troops; it replaces these classical forms of fighting with attacks on the environmental conditions of the opponent’s life. (…) The rapid development of military breathing apparatuses (in everyday language: cloth gas masks) shows that soldiers had to adapt to a situation in which human breathing became directly implicated in war events.2

In the aftermath of both world wars and the traumas they caused, gas emerged as a symbol of previously unimaginable atrocities. The Geneva Protocol of 1925 prohibited the use of chemical and biological weapons in international armed conflict. Later, in 1997, the Chemical Weapons Convention (formally: the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons), ratified by 190 states, came into force. Yet this treaty includes a significant exception for so-called „riot control.” Thus, the use of gas is no longer the most inhumane act of warfare but becomes a “humanitarian” tool in the hands of the police – a “soft” and “democratic” tool of repression.3 Violence is sanitized, reframed as order, and normalized through the language of care.

Tear gas is a chemical weapon designed to poison the air. Its effects are immediate and visceral: it burns the eyes, inflames the lungs, stings the skin. It seizes breath and floods the nervous system. Though rarely fatal, its impact can be severe—especially for children, the elderly, people with respiratory illnesses, or pregnant individuals. In many instances, protesters are struck directly by canisters, suffering life-altering injuries or death. Canisters are sometimes expired, or used at dangerously high concentrations. The air becomes weaponized. Breathing becomes a frontline.

Tear gas canisters are fired somewhere in the world every day. While in the Global North activists may encounter gas during demonstrations, it is usually an extraordinary, shocking event. In contrast, in places such as the Palestinian refugee camps of Aida or Dheisheh in the West Bank, tear gas is deployed multiple times a week—sometimes daily. There, canisters are repurposed: used to plant flowers, or turned into souvenirs sold to tourists. The gas no longer provokes alarm. Sometimes, it is even received with a sense of relief—it signals that Israeli special units have ended a night raid and are leaving the camp.

The first line of defense against gas is to shield one’s breath. Protesters rarely have access to professional equipment, so they are forced to improvise—assembling gas masks from materials available to them: plastic water bottles, soda cans, old T-shirts. This is a grassroots, consistent upcycling against toxicity of the state and systemic oppression. A refusal to surrender the air. Now that police brutality and gas abuse are on the rise, we can learn with and from those who have been resisting for years.

2. Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air, pp. 16–19.

3. See: T. Tehrani, “The Colonial Gas Machine: Teargas Grenades, Secular Humanist Police, and the Intoxication of Racialized Lives,” The Funambulist 14: Toxic Atmospheres.